Table of Contents

Who was Antonio Gramsci?

Antonio Francesco Gramsci was an Italian Marxist philosopher, journalist, linguist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, political theory, sociology, history, and linguistics. Moreover, he was a founding member and one-time leader of the Communist Party of Italy. He was imprisoned for being a vocal critic of Benito Mussolini and fascism and remained behind the bars until his death in 1937.

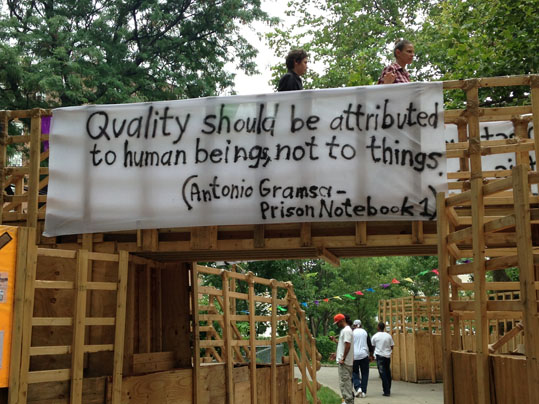

Gramsci wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis during his imprisonment. The notebooks cover topics, including Italian history and nationalism, the French Revolution, fascism, Taylorism and Fordism, civil society, folklore, religion, and high and popular culture.

Gramsci’s Idea of Cultural Hegemony

Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how the state and ruling capitalist class – the bourgeoisie (middle class) – use cultural institutions to maintain power in capitalist societies.

The bourgeoisie develops a hegemonic culture using ideology, rather than violence, economic force, or coercion. Hegemonic culture propagates its own values and norms so that they become the ‘values’ for all.

Cultural hegemony is therefore used to maintain consent to the capitalist order, rather than the use of force to maintain order. This cultural hegemony is produced and reproduced by the dominant class through the institutions that form the superstructure.

Gramsci’s neo-Marxism

Gramsci also attempted to break from the economic determinism of traditional Marxist thought, and so is sometimes described as a neo-Marxist.

Economic Determinism

Economic determinism is a socioeconomic theory that economic relationships (such as being an owner or capitalist or being a worker or proletarian) are the basis upon which all other societal and political arrangements in society are based. The theory stresses that societies are divided into competing economic classes whose relative political power is determined by the nature of the economic system.

Economic determinism is a theory typically attributed to Karl Marx – a German philosopher, sociologist, and economist. However, In the writing of American history, the term is associated with historian Charles A. Beard, who was not a Marxist but who emphasized the long-term political contest between bankers and business interests on the one hand, and agrarian interests on the other.

Theory of Cultural Hegemony

Cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who manipulate the culture of that society. Here the culture implies beliefs, perceptions, values, and mores. It so happens that the worldview of the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm.

In political science, hegemony is the geopolitical dominance exercised by an empire, the hegemon (leader state) that rules the subordinate states of the empire by the threat of intervention, an implied means of power, rather than by the threat of direct rule—military invasion, occupation, and territorial annexation.

Gramsci developed the notion of hegemony in the Prison Writings. Hegemony, to Gramsci, is the “cultural, moral and ideological” leadership of a group over allied and subaltern (inferior) groups. This leadership, however, is not only ethnopolitical, because it also needs to be economic, and be based on the function that the leading group exercises in the nucleus of economic activity. It is based on the equilibrium between consent and coercion. Gramsci first noted that in Europe, the dominant class, the bourgeoisie (middle class), ruled with the consent of subordinate masses. The bourgeoisie was hegemonic because it protected some interests of the subaltern classes in order to get their support. The task for the proletariat was to overcome the leadership of the bourgeoisie and become hegemonic itself.

Even though Gramsci was harshly critical of what he called the “vulgar historical materialism” and economism of Marxism, as a Marxist he assumed the fundamental importance of the economy. At this point, however, economic determinism seems to be a problem for the Gramscian concept of hegemony, and the ways the proletariat can become hegemonic.

According to Gramsci, only a hegemonic group that has the consent of allies and subalterns can start a revolution, which would mean that it is necessary to establish proletarian hegemony before the socialist revolution.

How can the proletariat have a dominant position in the world of the economy before the socialist revolution? How could the proletarians dominate the economy if the bourgeoisie is the class that controls the means of production and, therefore, controls the economy? Here Gramsci proposes that, in order to achieve a hegemonic position, the proletariat must ally with other social groups struggling for the future interests of socialist society, like the peasantry.

Counter-hegemony

The idea was to establish a new historical bloc (one that breaks the order established by the capitalist structure and the political and ideological superstructures on which the bourgeoisie relies) and a new collective will of the subaltern classes. This, in the words of Hyung Baeg, can be interpreted as “counter-hegemony” something that “is not a real hegemony in a strict sense, but economic, political and ideological preparations for hegemony before overthrowing capitalism or before winning state power.

One of the ways the proletariat must undertake such a task is through “organic intellectuals,” which for Gramsci, “are the dominant group’s ‘deputies’ exercising the subaltern functions of social hegemony and political government.”

Their “function in society is primarily that of organizing, administering, directing, educating or leading others.” These specialized cadres, formed both in the working-class political party and through education, had the duty of organizing, administering, directing, educating, or leading others. The formation of a national-popular collective is not an autonomous process, nor is the will of that collective. The organic intellectuals, who must be unrelated to the intellectuals of the bourgeoisie, must organize and mediate in the formation of the national-popular collective will.